An atypical reflection on death (through the view of Christianity).

I was volunteering at the park this past weekend. The crews I’ve been recently associating with are self-proclaimed theology nerds. We volunteer in an environment that is extremely tough on the emotional psyche, as many volunteer jobs tend to be – especially those which are service-focused. The theme of suffering and tragic death came up. It was stated:

For Christians: The nature of Jesus’ death transformed Death itself.

He had to be perfect1 in life, as to justify being saving from death2, and in doing so allowed the justification for all others to be raised.

I’d like to reflect on this within this post.

Music: Chihiro by Boone River

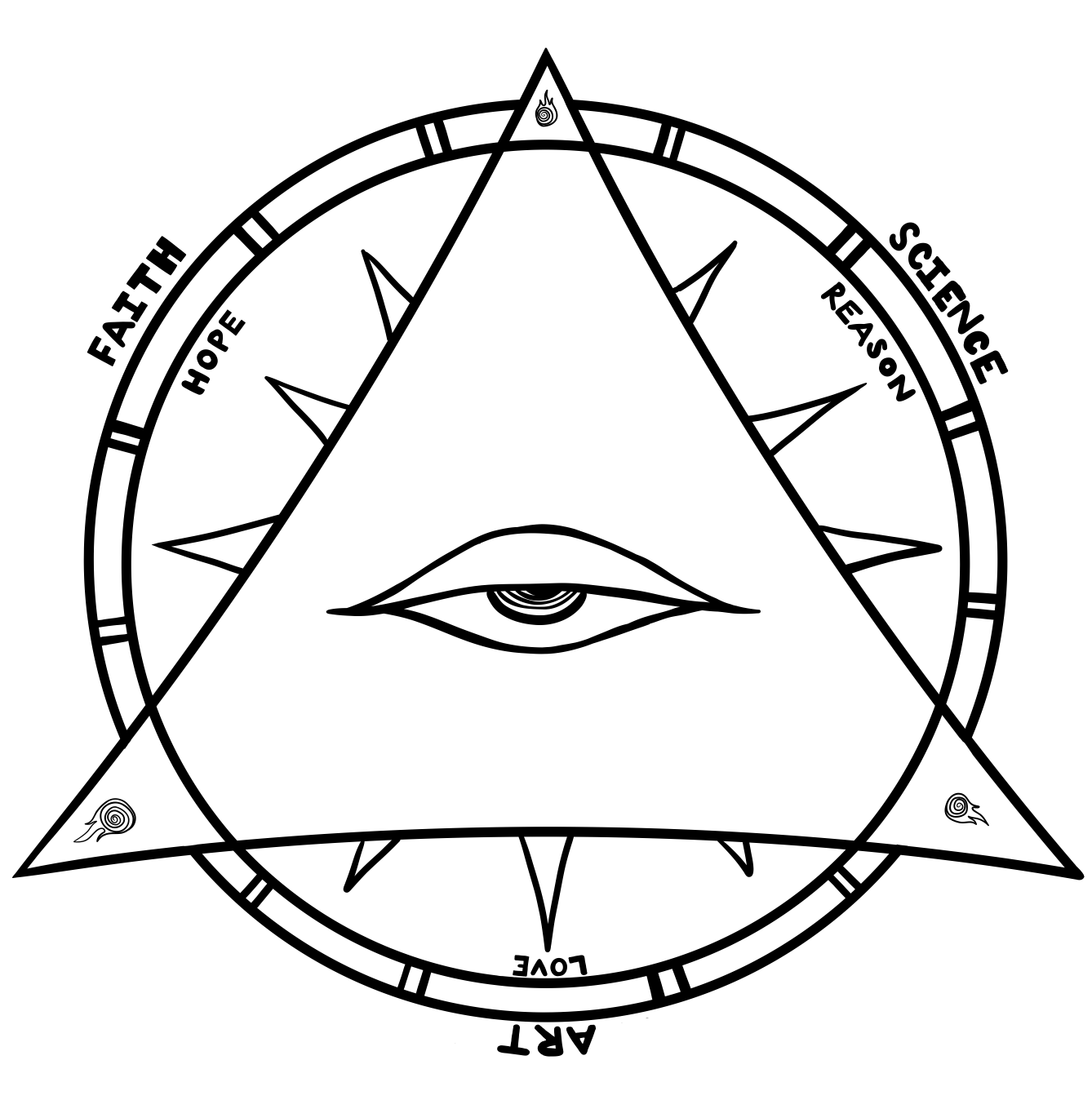

Across human civilizations, Death has never been a mere biological event but a force embedded in myth, ritual, and theological reflection. Societies have grappled with its meaning—annihilation, transition, return—structuring their moral and cosmic orders around its inevitability. In the Christian narrative, Death is neither an arbitrary fate nor an ultimate end but a reality intertwined with justice and restoration. The death of Jesus of Nazareth is not merely an execution but the moment in which Death itself is rewritten.

Christian thought inherited and reshaped both Jewish and Greco-Roman understandings of the afterlife. Where Jewish eschatology saw death as Sheol’s shadowed existence and Greco-Roman thought creatively imagined Hades’ varied fates, Christianity made a radical claim: Death was no longer final. It was not merely confronted but transfigured—turned from an end into a passage.

Yet this transformation had to be justified3. Jesus had to be perfect—not in some abstract metaphysical sense, but in a way that carried real consequence. Perfection, in this case, is not merely moral blamelessness but the full realization of humanity in unbroken communion with the divine. His was a being beyond corruption, and so, in the logic of justice, Death had no claim over Him. He alone was savable—not because He needed saving, but because, in Him, salvation from Death was a matter of justice rather than mercy. And yet, rather than standing apart from Death, He entered it willingly. Unlike mythic figures who evade mortality or overpower it from a position of strength, Jesus’ death is one of participation: He takes on the full weight of Death, not as a victim but as an agent, reconfiguring its meaning from within.

The Godhead and the Problem of Divine Action

Within Christian theology, divine action is not fragmented among separate wills but emerges from a singular divine unity. The challenge, then, is articulating how judgment, sanctification, and redemption unfold within the Trinity without collapsing into either rigid monotheistic determinism or a polytheistic division of labor. The crucifixion and resurrection are moments where this question becomes unavoidable.

The Father, traditionally understood as the source of justice, is both the Judge and the Executor (Executive), the one who enacts the divine order. Jesus, though fully divine, does not execute justice in the same sense but shares in judgment and assumes the role of sanctifier—the one who makes holy what was once unfit for divine presence. This work of sanctification is something He shares with the Spirit, who infuses divine life into what has been made holy.

Thus, the crucifixion is not simply an event of suffering or substitution but the fulfillment of a function within the Godhead. Jesus’ death sanctifies the human body, making it fit to bear divine presence. And in His self-emptying (kenosis), He does not act apart from the Father but fully assumes the Father’s will—the will not to condemn but to redeem. By willingly entering into self-voiding, Jesus does not oppose the Father’s justice but participates in it, transforming it into an act of ultimate mercy.

More than a theological abstraction, this understanding of divine action reshapes how one perceives the nature of the Godhead itself. The crucifixion and resurrection, then, can be understood as the moment in which the unity of the Godhead is revealed within time. The paradox is intentional: the Trinity was always one in being, yet in this moment, divine action converges in a way that history had not yet witnessed. Judgment, sanctification, and execution—once perceived as distinct functions—are unveiled as a single movement of divine love. Death is both suffered and overcome within the life of God, and through this, the divine economy is revealed not as a sequence of separate actions but as a singular will working toward redemption.

This is where divine action in Christianity diverges from other religious paradigms. The Godhead is not a collection of separate roles negotiating their functions, nor a single will imposing itself unilaterally. Instead, there is a dynamic unity: the crucifixion is neither something done to Jesus nor something He does in isolation, but an act of the entire Godhead, entering into and overcoming Death from within.

Death as Passage, Not End

Societies structure their understanding of Death through language, ritual, and cosmology. Christianity does not deny Death but redefines it. The crucifixion and resurrection introduce a rupture in its meaning: it is no longer a terminal point but a liminal space. What was once finality becomes passage; what was once the severance of life becomes, paradoxically, its fulfillment.

By entering into Death and emerging from it, Jesus does not merely exemplify endurance or martyrdom—His death and resurrection restructure reality itself. Death remains, but its function is altered. It no longer marks annihilation but transition, no longer separation but union.

This transformation, however, was not an arbitrary intervention but a necessary act within divine justice. In Christian thought, Death was not merely an oppressive force to be overcome but something that had to be engaged with, endured, and ultimately reordered. The process of sanctification—of making humanity fit for divine presence—hinged on Jesus fully entering Death, not as one subjected to its power, but as one who altered its very nature.

The Godhead and the Problem of Divine Action

Within Christian theology, divine action is not fragmented among separate wills but emerges from a singular divine unity. The challenge, then, is articulating how judgment, sanctification, and redemption unfold within the Trinity without collapsing into either rigid monotheistic determinism or a polytheistic division of labor. The crucifixion and resurrection are moments where this question becomes unavoidable.

The Father, traditionally understood as the source of justice, is both the Judge and the Executor (Executive), the one who enacts the divine order. Jesus, though fully divine, does not execute justice in the same sense but shares in judgment and assumes the role of sanctifier—the one who makes holy what was once unfit for divine presence. This work of sanctification is something He shares with the Spirit, who infuses divine life into what has been made holy.

Thus, the crucifixion is not simply an event of suffering or substitution but the fulfillment of a function within the Godhead. Jesus’ death sanctifies the human body, making it fit to bear divine presence. And in His self-emptying (kenosis), He does not act apart from the Father but fully assumes the Father’s will—the will not to condemn but to redeem. By willingly entering into self-voiding, Jesus does not oppose the Father’s justice but participates in it, transforming it into an act of ultimate mercy.

More than a theological abstraction, this understanding of divine action reshapes how one perceives the nature of the Godhead itself. The crucifixion and resurrection, then, can be understood as the moment in which the unity of the Godhead is revealed within time. The paradox is intentional: the Trinity was always one in being, yet in this moment, divine action converges in a way that history had not yet witnessed. Judgment, sanctification, and execution—once perceived as distinct functions—are unveiled as a single movement of divine love. Death is both suffered and overcome within the life of God, and through this, the divine economy is revealed not as a sequence of separate actions but as a singular will working toward redemption.

This is where divine action in Christianity diverges from other religious paradigms. The Godhead is not a collection of separate roles negotiating their functions, nor a single will imposing itself unilaterally. Instead, there is a dynamic unity: the crucifixion is neither something done to Jesus nor something He does in isolation, but an act of the entire Godhead, entering into and overcoming Death from within.

Suffering and Love

We are conditioned by what we love

Never abandoned by it, never left undisturbed.

Suffering is a mechanism by which Love consecrates us to IT.

The Love of The World is constantly seeking ways to consecrate us to it, even through suffering.

Suffering is an unavoidable part of human existence. It disrupts, isolates, and often appears meaningless. Why do we suffer? What purpose does it serve? The instinctive response is to resist it, to see it as an interruption of joy rather than something woven into the fabric of life itself. Yet, when seen through the lens of love—an unrelenting, unconditional love—suffering is not an empty void but a space where transformation occurs. At the heart of this perspective lies a radical idea: suffering has meaning because it is endured within love. In the act of creating and sustaining existence, the divine does not remain distant from suffering but fully enters into it. If love is what sustains life, then endurance—remaining present even in the face of suffering—is not passivity but an expression of that love.

To love unconditionally is to will the good of the other, even at personal cost. This is not a love that exists only when convenient but one that refuses to abandon what it has chosen. True love does not withdraw when suffering begins but remains, sustains, and transforms. In the same way that a parent does not abandon a sick child or a friend does not walk away when times are hard, divine love is not contingent on circumstances—it exists regardless of suffering.

Suffering often isolates. When we are in pain, it feels as though we are cut off from peace, from joy, even from others. But in this understanding, suffering is not a place of abandonment but a space where love is most deeply present. Love does not remove suffering but enters into it, transforming it from within. Love does not leave us in suffering; it meets us there and reshapes it.

This endurance of suffering offers a model. In choosing to sustain, to endure, and to love even when it is difficult, we participate in something far greater than mere survival. This is not passive resignation but an active consecration of suffering—turning it from something empty into something filled with meaning. Just as the hardest trials in life refine who we are, suffering has the power to reshape us, to deepen our capacity for love, for wisdom, for empathy.

This is not an attempt to justify suffering, but to reclaim it. It is not that suffering is inherently good, but that it is never meaningless. The pain we endure is gathered into something greater, into an enduring movement of love that wills good even in hardship. Even in darkness, the presence of love points toward hope, renewal, and transformation. In this light, suffering is a paradox: it is where pain and love intersect, where despair has the potential to give way to redemption. This does not diminish suffering’s reality but reveals that even in its depths, something more is at work. No experience, no matter how painful, is beyond the reach of love.

Ultimately, love and suffering are inseparable because love is unconditional.

To love unconditionally is to endure not only the joys but also the sorrows of existence. And if love sustains all things, then nothing—not even suffering—can separate us from it.

Thus, Christianity offers a vision in which Death is not destruction, but passage.

The loss becomes fulfillment.

The end, paradoxically, becomes the beginning.

Love. Be confident. Create. Grow.

@ CyberArtTime 2025

Footnotes

- The nature of perfection here is not fully understood and is subject for further consideration. ↩︎

- Jesus’ death fulfills not only His role in sanctifying the human body – making it fit to be the temple of God’s light – but also, through His willing participation in self-emptying (kenosis), He fully assumes the Father’s will to save all life. The crucifixion and resurrection can thus be understood as the moment in which the unity of the Godhead is revealed within time, made manifest as eternally one (an intentional paradox). ↩︎

- Assuming Divine Justice necessitates perfection cannot be obliterated. Yet, for justice to be fully enacted, obliteration must be brought to its completion. In the Christian worldview, Jesus’ death was intended as an abhorrent punishment meant to erase Him from history. Had the resurrection not occurred, His obliteration and descent into obscurity would have been the natural outcome. ↩︎

Leave a comment