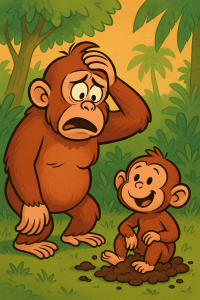

How one mother’s refusal to accept filth birthed the first sacred gesture of empathy.

Original Post: May 24, 2025

The first Homo sapiens didn’t just wake up one day and think:

“Hmm, time to wipe.”

No caveman stared back into the abyss of his own mess and thought:

“Out of sheer respect for myself and my peers, I must evolve.”

No… That’s not how it went down.

There is no way an early primate sniffed the aftermath of something gnarly it just relieved itself of and thought:

“This? This is so beneath me.”

He likely just cliched and scurried away to relax after a long day in the heat.

It wasn’t dignity...

It wasn’t instinct...

It wasn’t even shame…

Consider this: It was a mom.

THE Mom.

“Mama,” for those who prefer the formal title.

One frazzled, sabertooth-dodging mother looked at her grubby little spawn and thought:

“Oh… No! Absolutely not! Not in MY cave.”

And she didn’t do it for science.

Nor did she do it necessarily for progress.

She did it because she knew what that filthy little turd machine was capable of.

The spark that lit the fuse…

… wasn’t the harnessing of fire.

… wasn’t the flex of opposable thumbs giving rise to the creation of simple machines.

Theory of mind came to persons even long before a capacity for complex language.

Before stories.

Before grammar.1

Perhaps even before: “uh-oh…”

The spark that ignited the minds of our ancient ancestors was compassion.2

The kind that says: “I’ll touch the untouchable… for you.”3

We became Sapien4.

Not because we were always converging to this inevitability, but because someone else cared enough to clean us up along anyway.

Someone knelt down, sighed, and cleaned up the mess.

Not out of duty.

But out of love.

Love. Be confident. Create. Grow.

@ CyberArtTime 2025

- Theory of mind came before grammar: Cognitive scientists use the term Theory of Mind (ToM) to describe the ability to attribute beliefs, desires, and emotions to others. A skill essential for empathy and social living. Sarah Hrdy, an anthropologist, argues in Mothers and Others that ToM began not in abstract logic, but in the concrete demands of caregiving. Mothers who could anticipate their infants’ needs had an evolutionary edge. This was empathy with consequences. Frans de Waal extends this, showing that apes demonstrate rudimentary mindreading through grooming, reconciliation, and deception. The road to consciousness may have been paved by maternal intuition. ↩︎

- Core Thesis: The development of maternal caregiving behaviors, particularly in response to infant vulnerability and social uncleanliness, may have served as one of several socio-emotional scaffolds for the emergence of human theory of mind. The mother’s increasing ability to infer the internal needs of her offspring, especially in the context of disgust and nurturing love, provided a unique context where intersubjectivity could be selected for. ↩︎

- “I’ll touch the untouchable… for you.”: Psychologist Jonathan Haidt describes disgust as a moral emotion. In early human evolution, avoiding filth had clear survival value—but over time, disgust got moralized. Cleanliness became righteousness. But a parent wiping a child upends that code: they override disgust out of care. This moment of “I don’t want to, but I will for your sake” may represent an ethical pivot point, where love supersedes instinct, and behavior begins to be shaped by internal states, not just external triggers. ↩︎

- “We became Sapien.”: The Latin sapiens means “wise,” but our wisdom may have begun not with clever tools, but with shared vulnerability. Hrdy’s research shows that human infants are born unusually helpless—unable to cling, walk, or feed themselves—making them dependent on sustained, cooperative care. This may have forced early humans into deeper social interdependence, which then selected for emotional insight, patience, and perspective-taking. Compassion wasn’t a side effect of our evolution; it was possibly the engine. ↩︎

Leave a comment