Original Post: June 10, 2025

Though I said to myself,

"See, I have grown and increased in wisdom more than anyone who has ruled over Jerusalem before me; I have experienced much wisdom and knowledge."

Then I applied myself to the understanding of wisdom, and also of madness and folly, but I learned that this, too, is a chasing after the wind (hevel).1

For with much wisdom comes much sorrow; the more knowledge, the more grief.

Ecclesiastes 1:16–18

The Problem of Possession

Modernity has missed the mark by casting knowledge as currency and power as its logical consequence.

Truth, or at least its declaration, has been commoditized2, largely by a particular set of individuals jockeying for power who, in pursuit of narcissistic aims, employ the same mechanisms long used to reduce personhood to the ability to thrive in

[a social game that extravagantly rewards the few for their exercise of greed].

Such an orientation fractures the foundations wisdom culture was built.

When we treat knowledge as a private possession - hoarded, and its natural modes of connectivity3 disrupted to monetize sharing of inner self via economic models like the creator economy - we inadvertently sever ourselves from the essential conditions that make truth intelligible:

Genuine Relation

Profound Wonder

and

Deep Reverence

This idolatry of epistemic control has, paradoxically, birthed its own unique exile.

Despite vast expansions in scientific and technological understanding, we find ourselves no closer to existential peace.

In fact, we come to find that the deepening of "knowledge", especially in the form we have defined it in the modern era, as a subjective grasp4 of things which may be rationally known - often intensifies alienation.

Ecclesiastes anticipates this dilemma with precision.

"For with much wisdom comes much sorrow," is not as an indictment against learning itself, but as a warning against severing knowledge from grace.

Grace is what makes real understanding possible. It connects knowledge to humility, power to service, and selfhood to something greater than the self.

Wisdom, when uncoupled from love, doesn't liberate; it corrodes.

Insight becomes a source of grief when the knower forgets their fundamental belonging.

The pressing question, then, isn't how to physically recover paradise as a lost location, but rather how to rediscover it as an inherent mode of being.

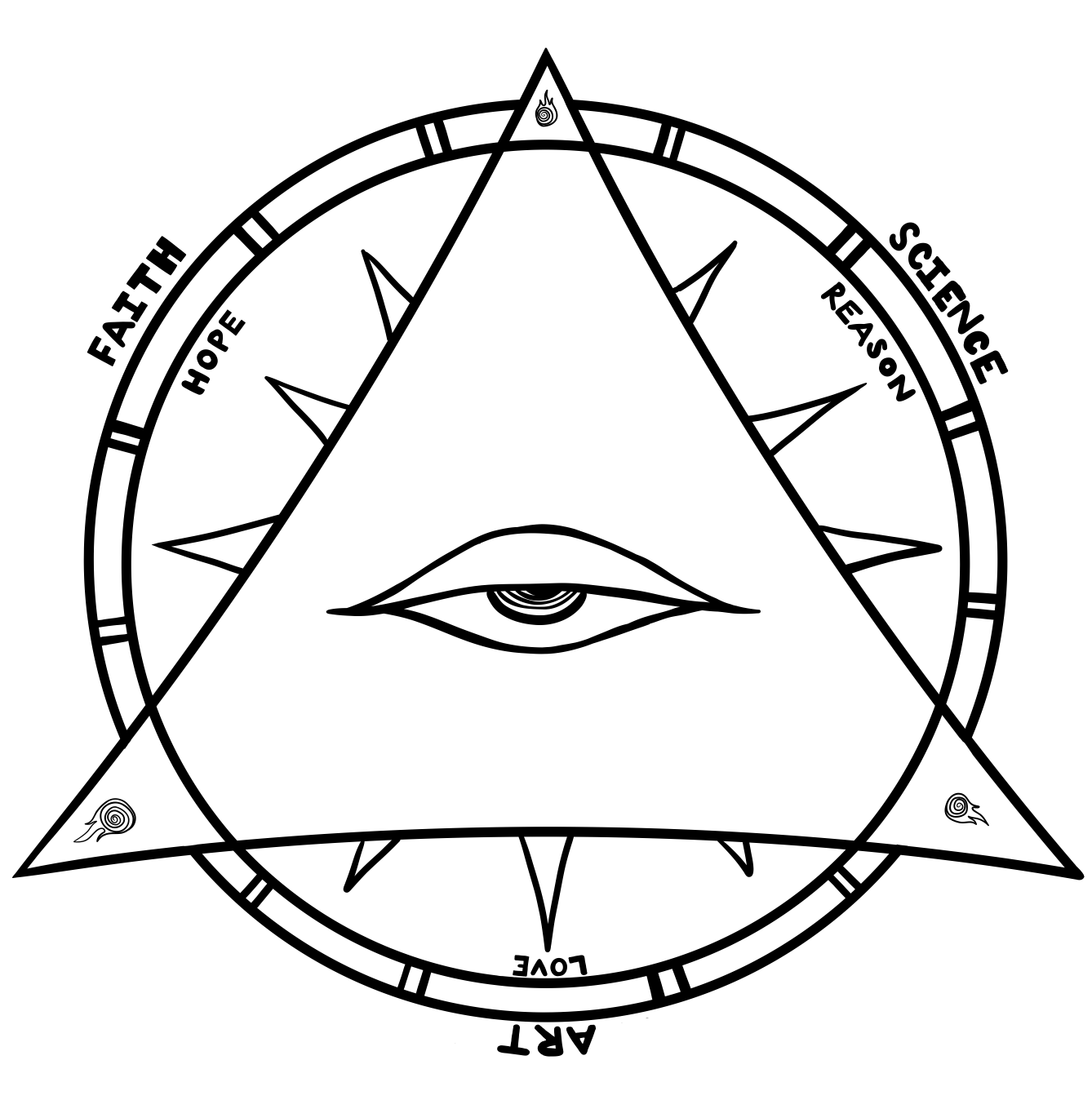

Christian theological anthropology powerfully insists that human beings are Imago Dei5, profound reflections of with the potential for divine orientation toward relationality and creative participation. It asserts that the core vocation of humanity is co-creation, as opposed to dominance.

To dwell in paradise, then, is not to escape the world, but to reinhabit it truthfully.

No longer as consumers of meaning, but as stewards of integration.

It means allowing reverence and humility to pervade our shared lives.

We require a return to the ancient vocation etched into our very being: to know for communion, not for mastery.

Paradise isn't a simplistic return to primitive innocence, nor a deferred eschatological hope.

It is the reawakening of the soul to its proper disposition: participatory trust.

Love. Be confident. Create. Grow.

@ CyberArtTime 2025

- Hevel: Often translated as “vanity,” is more accurately rendered as vapor, mist, or breath. It doesn’t mean meaninglessness; instead, it signifies something transient, elusive, and inherently difficult to grasp. ↩︎

- Truth Social: Truth Social – Wikipedia ↩︎

- “Modes of connectivity”: Connective Pathways ↩︎

- Hevel ↩︎

- Imago Dei (Latin for “image of God”) refers to the belief that human beings are created to reflect God’s nature. Rooted in Genesis 1:26–27, this idea affirms that each person bears inherent dignity and is called to share in God’s ongoing work of cultivating life, justice, and communion. ↩︎

Leave a comment